Day 28: Sheep And Goat Farming Part I: Housing And Care

Dear Student,

Sheep and/or goat farming is a fantastic way to help any family on their journey to self-sufficiency, and even a single animal can generate many and varied types of produce, including meat, milk, cheese, and wool.

Today, ovine (sheep and goat) dairy and meat are becoming more mainstream popular in North America than they have been for many decades. Boosted by the ever-increasing diversity of the population (coming from parts of the world where lamb, mutton, and goat make up a big part of the local diet than has been common in modern America), this growing market offers big opportunity to the small-scale farmer open to ovine farming.

Breed selection is important and depends, as always, on your particular area, climate, soil types, and natural pastures available. No matter where in the world you are, whatever climate profile you live in, there’s a sheep or goat breed that will thrive… you just have to do the research to find out what that is.

The other breed consideration is your end goal. Are you farming for meat, dairy, wool production, or a combination of two or all three? Again, no matter where you are and what your goal, you’ll be able to find a breed or crossbreed to suit your needs.

Local knowledge is often the most valuable and cost-effective resource when it comes to making the decision of what breed to raise. Join farming clubs, ask your local USDA branch, and talk to neighbors and other farmers to get the best education on what will or won’t work locally.

Step one when it comes to animal farming is to be honest with yourself about the responsibilities you’ll incur and making sure you understand the commitment and make it with eyes wide open.

You must ensure basic feed, water, and care to any animals in your charge—whether you’re sick, want a vacation, have a friend in town for the weekend, want to sleep in, or whatever. When it comes to taking on livestock, caring for them (or organizing for their care in your absence) will always have to be your first priority.

Sheep Farming

The Navajo Churro is a great choice for most climates, known for their hardiness and adaptability to most conditions. Introduced to the United States from Spain in the 1500s to feed the Spanish armies stationed in the Southwestern states, the Navajo Churro is considered to be the oldest sheep breed still commercially farmed.

The Navajo, Hopi, and other Native American tribes managed to obtain some from the Spanish, which they continued to breed and farm for centuries. The sheep-wool textiles still woven by these tribes are now much prized and world famous for both the designs and durability.

Many breeds will produce two lambs per year.

Mature lambs (young, nearly full-grown sheep) can have a harvesting weight of about 90 to 100 pounds and have a kill out percentage of 45%, meaning they’ll yield about 45 pounds of lamb on average.

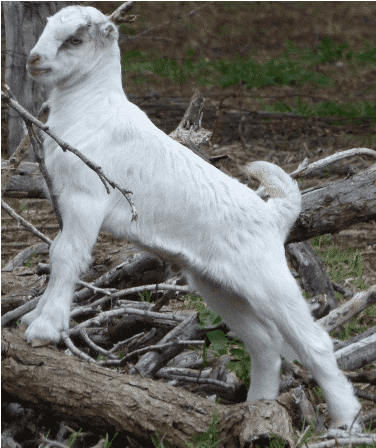

Goat Farming

Another 16th-century Spanish import (or, rather, a descendent thereof), the Lamancha (or LaMancha) goat breed is one of the most numerous types in dairy herds today.

Goats may be more versatile than sheep for the small-scale farmer… they eat a larger variety of feed and can be milked for longer periods throughout the year.

Goats produce between 6 and 12 pounds of milk per day, and they have about 285 lactation days per year, meaning you could expect anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 or more pounds of milk per year, depending on how intensively you farm them.

Like sheep, goats can be farmed for meat, milk, or wool.

However, fleece farming should not be considered a commercial enterprise unless you’re working with specialized hair breeds like cashmere, Angora, or Pygora.

Like mutton or lamb, goat meat is also showing a resurgence in popularity these days, and a market for either can be easily found no matter where you’re based.

Sheep And Goat Farming?

Can sheep and goats be farmed together?

Good news for the small farm holder: Yes, they can.

In fact, they can complement each other when it comes to making use of natural pastures, because they each have distinct eating habits. Sheep are grazers that like grass and broadleaved plants, clovers, and other legumes. Goats are browsers and prefer leaves, shoots, and young branches.

The easiest and cheapest way of feeding farm animals is to simply grass- or pasture-feed them, but this isn’t a wholly reliable method due to mitigating factors: climatic conditions, soil types, annual rainfall, etc. To prepare yourself to pasture-feed animals for the first time, you should seek out the advice of neighbors, the USDA, or other agricultural organizations in your area.

As long as you can offer a plentiful supply of forage for them both, sheep and goats are relatively easy to farm and give great diversity to your diet if farmed for home use.

As I said, both these animals have similar feed requirements, but there are a couple important differences in addition to the differences in pasture preferences.

The most important difference is copper in the diet. Goats almost always need a copper supplement, as they tend to feed off the ground (leaves, branches, etc.) where copper is not always available in useful amounts. Conversely, feeding supplemental copper to sheep is harmful and eventually fatal. Because they eat close to the ground and take in small amounts of soil as they graze, they get plenty of copper naturally.

If you’re farming both goats and sheep, you can overcome this diet difference by giving a “copper bolus” to the goat(s). It’s basically a copper pill that releases the mineral slowly over time inside the goat’s gut.

Care should be taken when letting sheep graze pure alfalfa or pasture with high clover content, especially when wet from dew or rain. Too much of these legumes can lead to bloating and dead animals very quickly… (It’s not normally a problem with goats.)

Important to remember is that both sheep and goats are highly social animals and need company to stay happy and healthy. While it’s possible to run a single sheep and a single goat together, it’s always better to have at least a few of each species if you have the pasture for them.

That said, sheep rams and billy goats should not be pastured or housed together. They will fight and injuries can be sometimes fatal, especially to the sheep. This is especially true during breeding times (rut).

Ovine Infrastructure: Designing Your Land For Livestock

Before you stock your land with any animals, you need to put in some infrastructure, including water systems and livestock handling facilities. You’ll also want to draw out your pasture lines before installing any fencing.

If you decide to replant your pasture land, again, do it before fencing. While it’s not impossible to do after, it’s much harder that way, especially if you are to use small pastures.

Housing

Handling facilities and shelters can be fairly rudimentary and cheap to erect.

Some of the essentials for sheep and goats include:

- Shelter from rain for goats; they don’t like the wet and won’t thrive if left to the elements.

- Shelter from sun for sheep; they can’t be left unprotected from the worst heat of the day.

- Fenced in pasture. When it comes to fencing, barbed wire is common, but I prefer sheep netting or electric fencing, and this must be put up only after your pasture system has been carefully designed.

- A small corral or pen for administering medications and carrying out basic care, like hoof trimming and deworming. A disinfectant foot bath built into the chute leading from pasture to corral will ensure the animals’ feet are regularly sanitized and remain hard and healthy.

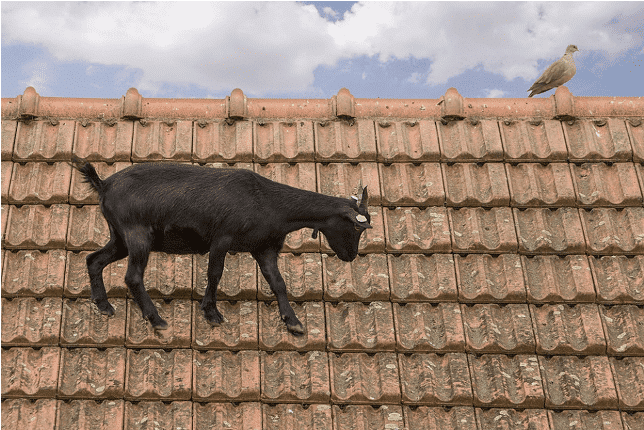

Remember, goats are natural climbers and will torment you to no end with their escapes if your fencing is not good enough. If they do escape, they’ll eat anything they can get their teeth into—they can cause serious damage this way. If you’re daunted by great goat escapes, you might consider sticking to sheep. Consider the difficulties of getting a goat off your roof… sheep won’t put you through that!

At lambing or kidding time, bring your animals into a shed at night and during bad weather. Young lambs and kids are more fragile to cold and wet conditions, and they can die easily if exposed in harsh conditions before they have their first drink of milk (colostrum).

Housing the flock at nighttime also means that you can easily check the breeding herd for any problems before bedtime or throughout the night if necessary.

Care

With the help of your neighbor or agricultural extension officer, make up a calendar of what you should be doing when throughout the year and mark any specific days for certain tasks.

Note all things, like routine health checks and medical treatments (deworming, hoof trimming), or when you should put the rams in with the ewes.

Hoof trimming is an important chore. Lame sheep or goats will struggle to forage or graze, leading to weight loss and poor body condition. This ultimately translates to lower milk and meat yields and subpar wool.

Include in this calendar notes on what to look out for at different times of year, like when a disease may be more prevalent due to climate.