Day 2: Permaculture Design And Designing Your Homestead

Dear Student,

The study of efficiency and abundance in natural systems is an ancient concept, but one that we’ve drifted away from in the last 100 years.

Current estimates show that half the soil of arable land worldwide has been lost to erosion, salt-panning, and pollution since the 1950s. Vast portions of Earth’s forest and rainforests have been clear-cut and farmed using unsustainable practices, leaving the areas barren and degraded in less than a decade of use.

The use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides, and unsustainable plowing techniques in vast mono-cropping systems eventually causes biocide (death of all elements in a system).

“A nation that destroys its soils destroys itself.”

–Franklin D. Roosevelt

The answer to this is simple, though. The model for true sustainability can be found all around us in natural systems.

Mother Nature’s healing efforts can be greatly assisted by the intelligent assembly of natural systems; this strategy is often referred to as permaculture. Through permaculture, your production increases in yield and resilience while building soil and biodiversity year upon year, simultaneously reducing time and resources spent.

No space is too small to start in, but more space means there are larger-scale options available to you.

What Is Permaculture?

Permaculture is a portmanteau word created from “permanent agriculture.”

Bill Mollison, known as the father of permaculture, co-created this concept with his partner David Holmgren back in 1978. He explains, “Permaculture is about designing sustainable human settlements. It is a philosophy and an approach to land use which weaves together microclimate, annual and perennial plants, animals, soil, water management, and human needs into intricately connected, productive communities.”

Sustainability is a core principle of the permaculture concept. A sustainable system produces more energy than it consumes, leaving enough surplus to maintain and replace the system over the lifetime of its components. This is the ideal scenario.

How To Create Permaculture On A Micro-Farm

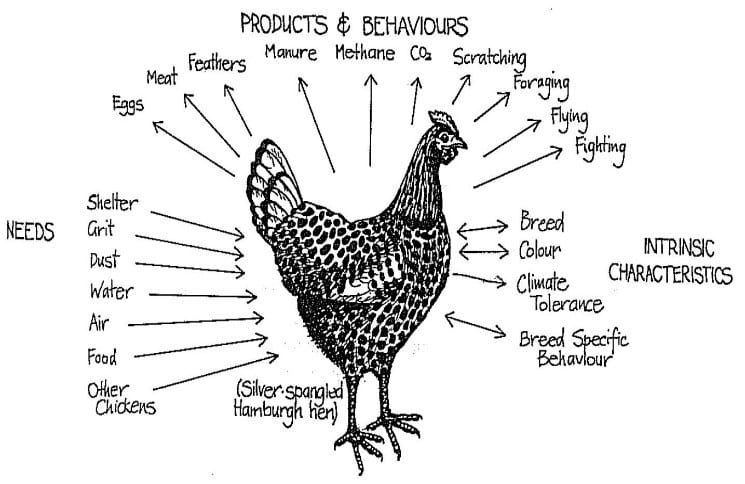

Each element in your self-sufficient endeavor should have at least three uses and little or no actual waste. For example, a chicken has many uses; it consumes kitchen wastes, reduces pests, provides meat, eggs, feathers, etc.

Pollution is a product not used by something else, and this is something you should strive to avoid. Aside from creating unusable waste, it means you have to do more work to deal with it. How will you get rid of wastes that can’t be dealt with yourself? You’ll have to collect it all and presumably take it off your land to an authorized dumpsite.

Ideally, you should try to find a way for all leftovers or wastes from one system to be used by another system on your farm. To do this, you’ll need to cultivate some perennial plants and trees… and know how to put them to work for you within your natural systems.

It may become useful for you to create a flowchart to graph out how wastes can be reused throughout your systems.

For example:

-Bruised fruit from the orchard is used to feed the pigs…

> The pigs’ manure is used to fertilize the vegetable garden…

>> Vegetable garden wastes are fed to the chickens…

>>> Chickens free roam around your fruit trees so their manure fertilizes your orchard and they reduce pests that compromise your trees…

Find synergy and use it to your advantage wherever you can.

In the end, you harvest a bounty of pork, eggs, fruits, and vegetables that took few off-farm resources to produce.

The idea is to create a system of agriculture that is self-sufficient, requires little to no work (by humans) to maintain, improves the land, and produces a product (food, wood, fiber, animals) that humans can use.

Designing Your Farm Layout

Use maps to sketch out your design concepts, but also pay attention to the actual landscape itself.

You can sketch a map of your backyard by hand, or for larger areas you can use topographical maps, Google Earth or Google Maps, or survey your parcel of land yourself.

Here’s how…

Sector Planning—Zones

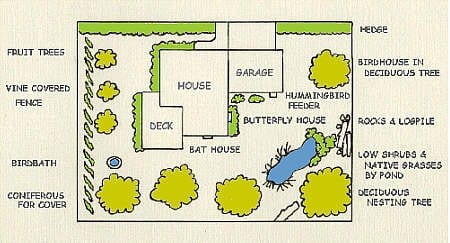

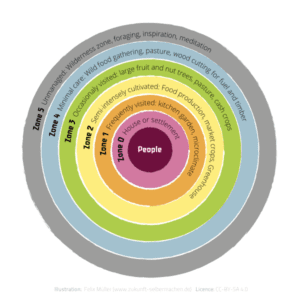

Intelligently designing and laying out your working areas can save greatly on time and effort.

Using zones, you can lay out your systems practically by placing elements that require the most attention (like a garden or chicken coop) closest to where you live, reducing time spent walking to and from.

Not everyone will have five zones, of course… some may only want one zone. Remember, your homestead should be tailored to your needs.

Zone 1: Visited several times per day (starts at the back door)

- Your home is at the center of Zone 1, which is surrounded by:

- Herbs

- Vegetable garden

- Most of your built structures

- Intensive growing plots

One of the most economical uses of space for a kitchen garden is a mandala garden, which is circular and lays out a path of “spokes” from which you can get closer to each crop for maintenance, harvest, etc. A mandala garden takes about 40 minutes to set up once you’ve become familiar with the process, and an intensively packed mandala can feed one person per season. If you live in a cold climate, you might want to plant an extra mandala or two to see you through the winter.

Zone 2: Visited twice a day

- Intensive cultivation of main crops

- Heavily mulched orchard

- Mainly grafted and selected species for maximum production

- Dense planting

- Some small animals: chickens, ducks, pigeons

Zone 3: Visited once to several times per week

- Often connects to Zone 1 and 2 for easy access

- Some mid-sized animals: goats, sheep, geese, bees, dairy cows

- Hardy and native species

- Un-grafted trees for later selection and grafting

- Animal forage site

- Windbreaks, firebreaks

- Spot mulching

- Nut tree forests

Homesteader Hack: Put 20% to 30% of your animal pasture into productive trees and lose no pasture-grazing yield per acre, yet gain additional yield of fruit, timber, or tree forage.

Zone 4: Visited a couple times per month

- Timber for building

- Firewood

- Mixed forestry systems

- Large and herd animals: cattle, deer, pigs

Zone 5: A permanent wild area

- Timber

- Hunting

- Wildlife refuge—seeps nutrients into the other zones naturally

Orientation

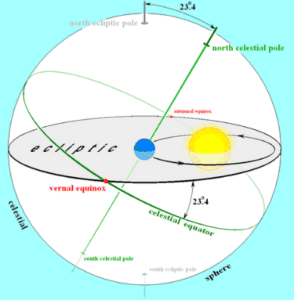

This refers to the placement of an element to face the sun or shade. To do this properly, you need to think about how the sun travels through the sky.

This refers to the placement of an element to face the sun or shade. To do this properly, you need to think about how the sun travels through the sky.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the winter sun rises in the southeast and sets in the southwest, so here you want to orient houses and gardens facing south to take full advantage of the sun’s energy.

In hot Northern Hemisphere climates, you’d orient houses to face the wind for its cooling effect, reducing windows on the southern side of the house to prevent overheating.

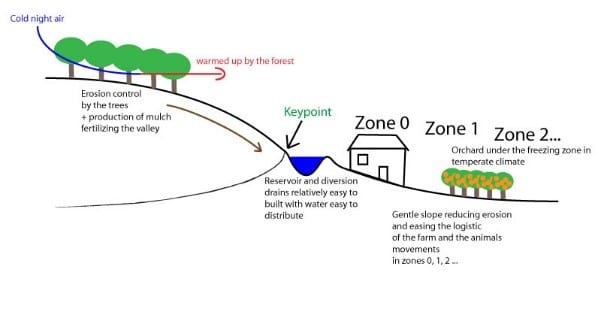

Slope

Slope is a big consideration when placing elements, as gravity can work in your favor if you plan correctly… or against you if you don’t.

- Water can be pumped to storage tanks by windmills or solar pumps and then gravity-fed to gardens when you need it.

- Mulch and other materials can be kicked downhill by chickens and other animals, spreading it for you.

- Nutrients from animals can trickle downhill with no effort from you.

But, again, you must plan carefully, because, of course, if you’ve got to work hard to get things moving uphill.

Don’t forget to consider aspect, the orientation of a slope. A slope facing the sun will get a lot more solar radiation than a slope on the shady side of a hill.

House And Infrastructure Placement

You don’t want to situate your house high on a hill. Mid-slope is better for easy water pumping, shorter access roads, and safety from wildfires.

Taking into account the above on orientation, make sure your house is oriented correctly to the sun and wind for your aspect and climate.

When placing roads, try to run them along the same contour line (that is, at the same elevation), which prevents erosion and assists in water harvesting.

Position water-harvesting earthworks and swales to ensure correct year-round hydration of house and outer zones.

Patterns

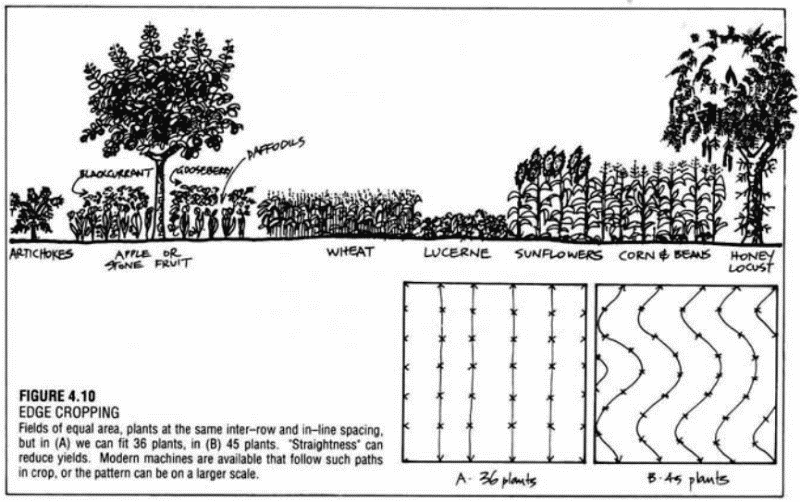

The Edge Effect

In biology, all life around edges is more productive; where two ecosystems meet, you inevitably find a greater number of species.

Hence, creating patterns with more edge in your systems will almost surely increase productivity.

How do you get more fruit trees into your orchard without reducing the distance between trees? The edge effect.

You can easily extend crops by shifting the shape of the rows you create. Take a look at the illustration below. The curved rows of the trees in frame B allow for 25% more trees to be planted with no loss in distance between the trees.

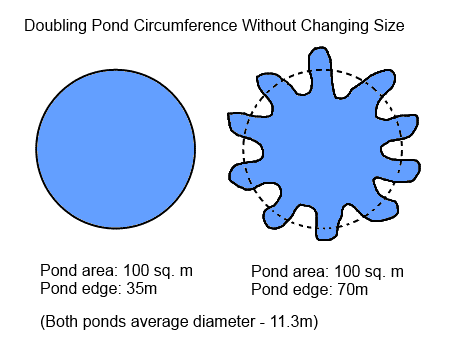

Likewise, changing the shape of a pond without changing its area can increase the productivity of the pond. Take a look at the diagram below. The round pond has less circumference than the star-shaped pond. The star-shaped pond has more habitat space for niches and can support more water life.

For this same reason, it’s better to have two small ponds rather than one giant pond—and that logic can likewise be applied to any element in your garden. Four small mandala gardens are better than one large one, etc.

Swales: Water Harvesting On Contour

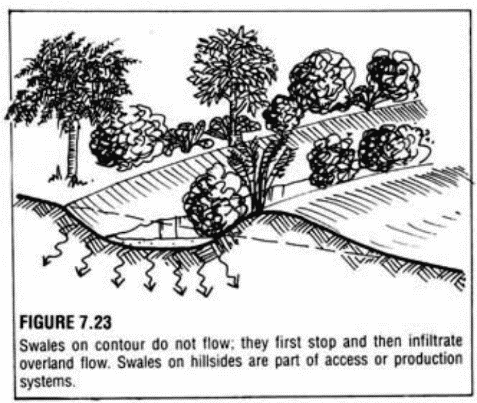

Swales are one of the most important earthworks features you can construct on your property.

Swales are tree-growing water catchments that run on contour (on the same elevation line; see illustration below). They are designed to stop and absorb all rainfall on your property, thereby rehydrating your water table and transporting nutrients throughout your property.

Ponds, dams, swales, and other water catchments increase fertility, yield, and resilience, no matter their size.

Combining Systems

While not necessarily a pattern concept, another way to increase the overall yield is to combine complementary systems.

For example, if you put 20% to 30% of your pasture land into productive trees, you won’t lose any pasture-grazing space per acre… but you’ll gain additional yield of fruit, timber, or tree forage.

Dispersal Of Yield Throughout The Year

An orchard with only one variety of fruit usually has one narrow fruiting timeframe, meaning it all ripens at the same time. It must all be picked and used quickly… which isn’t ideal. Either it means you aren’t getting the best use out of your crop (putting too much into canning, jams, etc.) or are forced to find a buyer to take the excess food at wholesale prices.

There are several easy solutions to this dilemma:

- Plant early, mid, and late varieties of different species, which is possible with just about all fruit trees. This allows fresh fruit over a much longer portion of the year.

- Plan for the same varieties in early and late ripening situations, using glasshouses and thermal heat mass to kick-start germination or fruiting.

- Select long-yield varieties.

- Increase the diversity of crops by using leaf, root, and seed, as well as fruit as products.

- Use self-storing varieties, tubers, and seeds.

- Use perennial rather than annual crops.